Short Teaching Module: Global Approaches to Maritime Trade in Colonial North America

Overview

Traditional narratives in American history, especially in colonial history, tend to focus primarily on British policy and British trade networks. Taking a global approach to the maritime trade of British America in the colonial era provides a better understanding of the actual economy, however. British America was influenced by the global economy of the 17th and 18th centuries, which also shaped the political and social changes that defined the colonial era in British America, such as the American Revolution. A global approach allows students to have a fuller picture of these events than more focused regional or national approaches.

Essay

For many decades, colonial American history was dominated by a nationalistic and regionally divided narrative that focused almost solely on the British Empire, and saw the colonial economy as dominated by British merchants and consumers. Atlantic World historians broadened the narrative, applying an oceanic approach to the period and considering other powers beyond Britain. David Armitage, Bernard Bailyn, and others led the way for an entire group of scholars such as April Lee Hatfield and Wim Klooster to redefine the history of colonial America in a broader and more complete way. But regional divisions still remained important to the overall narrative of colonial American history, such as those that saw the New England colonial economies as different from the Middle Colonies like Pennsylvania and Maryland.

When one zooms further and further out, however, such differences seem less and less important, and the distances between ports such as Boston, New York, and Philadelphia also seem to become smaller and smaller. Global historians have recently provided new ways for historians of colonial America to approach their subject. Rather than try to tackle the entire world, some are starting to examine smaller geographical locations within a global perspective. This can mean examining a single city or region and how its history was influenced by global history and/or how that city or region influenced global history. Others examine how a single commodity or group of people influence world history, such as Sven Beckert’s history of cotton’s rise as a global commodity and how it influenced and altered the entire world’s economy. In such histories, the narrative changes to favor similarities over differences and connections over separation. National and imperial borders, while still present in the narrative, fade into the background, and individuals or groups of individuals feature as key actors in a global story.

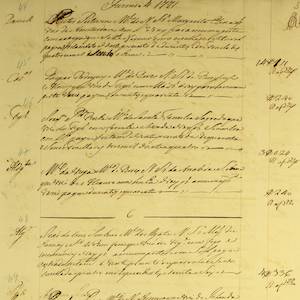

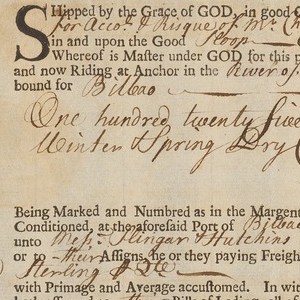

Such approaches can be applied to colonial British America. Using merchant records including letters, invoices, bills of lading, and even the smallest pieces of paper buried in archival folders, a global story of illicit commerce, global commodities, and a surprisingly cosmopolitan colonial economy appears. Taking Boston, New York, and Philadelphia as examples, one can find an enormous number of documents and sources that describe consumer markets as global. Commodities such as tea (from China), spices (East Asia), chocolate (Africa and South America), sugar (Caribbean and South America), textiles (South Asia and Europe), and even human cargo (enslaved Africans and European indentured servants) mixed with local products and workers to form an economy not too different from our own modern, globalized economy. The fact that these three cities participated in a globalized economy is not so surprising when we look at the early modern economy as a whole, for commodities and people moved throughout the world with both speed and scale. Tea was one such commodity that fundamentally altered the global economy and created demand for other goods such as sugar and porcelain.

Residents of colonial America were part of these global economic currents, and global economic processes eventually caused social, cultural, and political changes in colonial era British North America. One of these processes was maritime trade. More often than not, historians have focused on the mercantilist policies of Britain, in which the colonial economy was supposed to depend on the metropole (Britain) for access to goods, commodities, and credit. Legally, British Americans were supposed to trade only through Britain for goods from other parts of the world. But when one examines the archives that merchants left behind, the story is far more complicated. In fact, there seems to be ample evidence that direct trade with Britain may have been less important to the colonial economy than direct trade with the rest of the world.

In these individual merchant papers, one finds innumerable examples of communication and exchange between British Americans and non-British subjects in both non-British colonies and other empires such as the Portuguese and the French. One Boston merchant, Caleb Davis, established a lucrative mercantile business trading throughout the Atlantic with British and non-British destinations alike. He even set up his own brother in San Domingue in order to access French sugar and molasses. This trade was far from legal, and if had been discovered, he would have faced significant financial penalties. He certainly recognized this, as his shipping records listing ships headed to and from “the West Indies” obscured their real destination and origin of San Domingue from the British Customs officers, a strategy he shared via letters with his brother and ship masters.

Micro-level sources are not the only way we can find evidence to illuminate invisible (or what was intended to be invisible) economic activity such as smuggling. Imperial sources, such as British Customs Records, capture only what was reported to officials, but they can still be useful. As Britain had laws against direct trade between the colonies and other empires, merchants were not entirely forthcoming to British customs officials on all their trade, as the example of Caleb Davis highlights. But if we also examine non-British imperial sources, such as Portuguese tonnage tax duty records, then compare that with the data collected by British officials, we can quantify that which is missing from the official records of the British Empire. For example, Philadelphia maintained a robust trade with Lisbon, trading wheat for salt and wine. Some of this was at least tolerated by British officials, as we do have data from the British statistics of direct trade between the two cities. According to British records, Philadelphia sent a yearly average of 68 ships to Lisbon from 1769-1774. According to Portuguese records, however, an average of 118 ships arrived from Philadelphia each year, nearly double the official recorded number from the British perspective. Comparing British and Portuguese sources thus provides a fuller picture of the colonial American economy.

Understanding how intricately connected the colonial American economy was to global economic currents puts the American rebellion in an altogether different light. When the British attempted to control and end the clearly robust illicit exchange between American merchants and the rest of the world, it is no surprise that there were protests, riots, and eventually political revolution, and that a significant portion of the populace supported such a movement. Although it is the best known, tea was only one of these commodities. Even the tiniest of transactions for things like salt transcended imperial borders, and colonists were deeply imbedded within a global economy. Separating them from that economy caused discontent and even anger against the British Empire, resulting in the American Revolution.

Primary Sources

Credits

Jeremy Land is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Helsinki in the Economic and Social History unit of the Faculty of Social Sciences. He received his PhD from Georgia State University in 2019. He also serves as the meetings coordinator for the Economic History Association, and his first book titled, Colonial Ports, Global Trade, and the Roots of the American Revolution will be published with Brill in late 2022 or early 2023.